E-Mail Us:

railarchive@mail.com

Text and photo images

©2013 Richard Leonard.

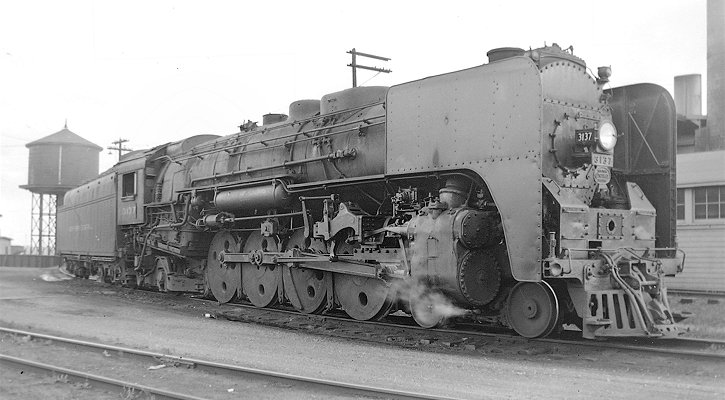

The New York Central was known as the "Water Level Route" because its main line between New York and Chicago followed the Hudson and Mohawk rivers and the southern edge of the Great Lakes. For main line freight service it relied heavily on the 4-8-2 wheel arrangement, which it styled the Mohawk type. The later Mohawks (classes L-3 and L4) were equally at home in heavy freight or fast passenger service. No. 3137, which I photographed at Mackinaw City, Michigan, in August of 1955, was a member of class L-4b, the last set of 4-8-2s to be acquired by the NYC She was erected by Lima Locomotive Works in 1943, had a boiler pressure of 250 pounds per square inch and 26x30-inch cylinders, and exerted 59,900 pounds of tractive effort. The total weight of both locomotive and tender was 766,700 pounds. Class L-4b was the first class on the NYC system to feature the multiple-bearing crosshead instead of the "alligator" type still used on the J-3 and L-3 classes. (The multiple-bearing crosshead also appeared on the Niagara 4-8-4s and the P&LE A-2 2-8-4s.) This photo appears in The Steam Locomotive's Energy Story by Walter Simpson, published in 2021 by The Chesapeake & Ohio Historical Society, Inc.

By the time I was photographing steam, locomotives like No. 3137 had been displaced from most of NYC's main lines and relegated to more lightly traveled lines like the Mackinaw City branch. However, at this time there was still freight traffic by ferry across the Straights of Mackinac providing a connection with the Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic (later absorbed by the Soo Line). Upon the demise of Penn Central (merger of the New York Central and its arch-rival, the Pennsylvania Railroad), the Mackinaw branch was not included in the formation of Conrail, though portions are still served by Lake State Railway.

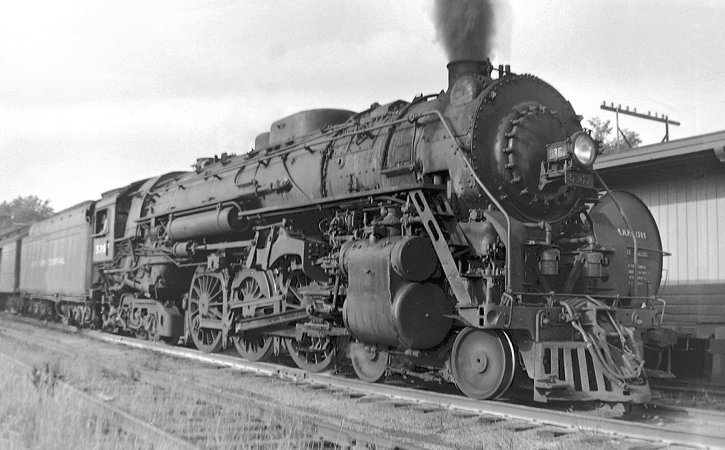

Although the Central's L-3 and L-4 classes were designed as dual-service power, the older 4-8-2s of the L-1 and L-2 classes were freight engines. A roster published in 1940 lists 135 members of class L-1, built beginning in 1916, and 300 engines in class L-2 erected 1925-1930. In August 1953 I photographed No. 2967, a representative of class L-2d, in the yards at Lansing, Michigan, on the line between Jackson and Bay City. A 1929 product of the American Locomotive Company, No. 2967 had 25½x30-inch cylinders and 69-inch drivers, and carried a boiler pressure of 225 pounds per square inch. With a locomotive weight of 370,150 pounds she produced 60,150 pounds of tractive force, to which a booster added another 12,400 pounds. The L-2d class had a grate area of 75 square feet, around 4600 square feet of evaporative heating surface, and 1930 square feet of superheating surface.

|

|

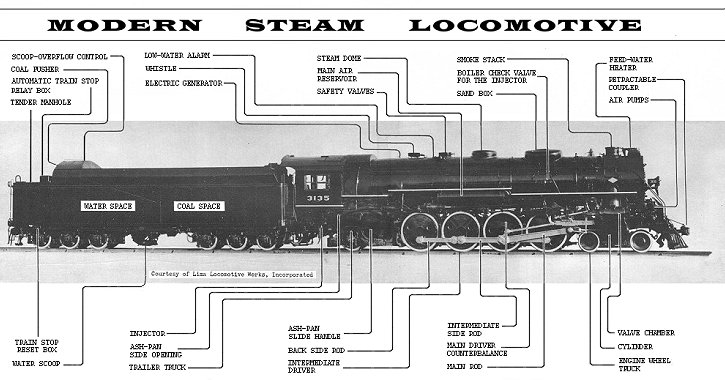

"The fireman of the modern locomotive," the course begins, "must have a thorough knowledge of firing methods that must be pursued in order to evaporate as much water into steam as possible with every pound of coal burned." The "modern locomotive" chosen to illustrate firing procedures was this Lima Locomotive Works builder's photo of New York Central's Mohawk No. 3135, sister engine to No. 3137. She appears in this view minus the smoke deflectors visible above.

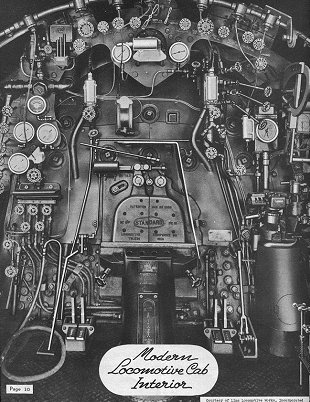

Firing a large steam locomotive is an art requiring constant attention to the engine's performance, understanding of the use of a variety of types of equipment, and — as the course stresses — close cooperation between the fireman and the engineer. "One steam failure resulting from poor firing or lack of crew cooperation is far reaching, and may tie up an entire section of the railroad system. The average person does not realize how much experience, information, and teamwork are necessary to bring about an 'on-time performance.'" The textbook includes this illustration of a steam locomotive backhead or cab interior, also courtesy of Lima Locomotive Works and presumably from the New York Central's Class L-4 Mohawk type. The daunting array of pipes, valves and gauges is further testimony to the skill and expertise needed to keep the modern steam locomotive operating at its peak of efficiency and performance. |

|

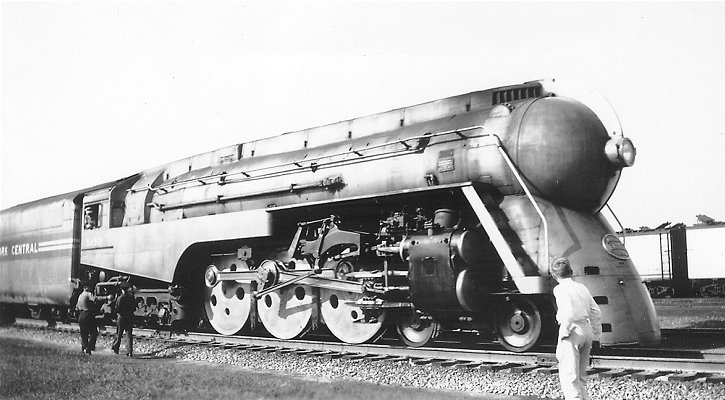

The New York Central's class S-1 4-8-4s, erected by American Locomotive Company in 1945-46, were considered by many to be the apex of steam locomotive design in North America. Intended for long-distance, heavy duty passenger service over the Water Level Route, they rivaled the emerging diesel in horsepower, efficiency and availability. Sadly, they had little chance to prove their mettle before the NYC opted for internal combustion in place of steam, and were soon demoted to local passenger service. I witnessed one of these Niagaras (as the Central called its 4-8-4s) in that role in the autumn of 1953 as it brought my maternal grandmother's casket into Butler, Indiana, for interment.

On a visit to the Englewood terminal in Chicago in July 1954, I photographed Niagara No. 6003. These engines featured a 14-wheel "pedestal" (PT) or "centipede" style tender which carried 18,000 gallons of water and 46 tons of coal. Like other high-speed New York Central steam power, the Niagaras were equipped to scoop water on-the-fly from long pans set within the rails. The S-1s had roller bearings on all axles and also on the side rods and Baker valve motion. They were designed to accept either 75-inch or 79-inch driving wheels depending on their projected usage. The first example, S-1a No. 6000, came with the smaller drivers as a "dual service" locomotive to satisfy requirements of the War Production Board, but the 25 engines of the S-1b class that followed all came with the larger drivers intended for passenger service, and No. 6000 was also converted to the 79-inch size. (Larger driving wheels mean the locomotive is capable of faster speeds, but tractive effort is reduced.) The Niagaras had a boiler pressure of 275 pounds per square inch, 25½x32-inch cylinders, and a tractive effort of 61,570 pounds. Their trailing truck supported a firebox with 101 square feet of grate area. This, combined with an evaporative heating surface of 4,819 square feet, produced about 6,000 horsepower at 40 miles per hour, the equivalent at that time of four diesel units. The S-1s were fitted with a diesel-like air horn as well as a steam whistle, which sometimes fooled photographers lying in wait for a shot of this relatively short-lived breed of iron horse. |

|

If any steam engine could be said to have been the trademark locomotive of its owner, the New York Central's Hudson type 4-6-4s would qualify. These locomotives handled passenger trains throughout the system, regularly hauling heavy main line limiteds at speeds over 90 miles per hour on level track. During 1946-1951 our family lived in Adrian, Michigan, and I can well remember the sight and sound of these engines heading a speeding stream of New York Central trains on the main line west of Toledo during a train-watching day with my father. The Central's Hudsons were the prototype for countless model trains which delighted boys — and men — across the continent.

I caught Hudson No. 5367 at Gaylord, Michigan, in August, 1953, heading up the Sunday-only Timberliner bound from Mackinaw City to Detroit. Originally the Michigan Central's No. 8222, she was one of 75 members of class J-1d outshopped by American Locomotive Company, located along NYC trackage in Schenectady, New York, in 1929-30. No. 5367 sustained a steam pressure of 225 pounds per square inch and had 25x28-inch cylinders. Like all of New York Central's Hudsons except the 20 operated by subsidiary Boston & Albany, she boasted high 79-inch driving wheels. All Hudsons had a booster engine in the trailing truck for help in starting heavy trains. With the booster operating, the J-1s produced 53,250 pounds of tractive force. No. 5367 was also assigned to the Michigan Central's Canadian operation, known as the Canada Southern. Viewer Tom Rock has supplied a photo of her at the head of a mail and express train at Windsor, Ontario, attributed to Walter Taylor. No. 5367 was retired in October, 1953.

What a loss that, of the 275 Hudsons owned by the New York Central System, not one example was spared the salvager's torch. Above we see J-1d Hudson No. 5314 in the dead line at the Detroit engine terminal in March 1954 — her number not yet crossed out and her rods still intact, but her fate sealed along with that of her companions on the adjacent tracks. |

|

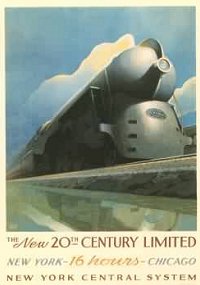

Design of the New York Central's Hudsons reached its epitome in the J-3a class, Nos. 5405-5454, delivered by ALCo in 1937-38. The final group of ten were streamlined for the Twentieth Century Limited. Henry Dreyfuss's famous styling for the Century, featuring a finned bullet nose resembling an ancient warrior's helmet, has been hailed as an icon of art deco industrial design. Although my father, Dr. R. D. Leonard, was an avid New York Central fan and train-watcher, he seldom attempted photography with our ancient folding cartridge Kodak. He left a small collection of New York Central steam photos from the 1930s, but because they were the work of other photographers I had not considered them for use in this Archive. (You can view them in my New York Central Collection.) I was delighted, reviewing Dad's collection, to suspect that he had taken this photo of one of the streamlined J-3s, No. 5450, in 1938 or 1939. My suspicions were confirmed in correspondence with my uncle, the late Alan B. Campbell of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, who appears in the picture as the young man intently examining the locomotive's pilot.

The scene is Chicago's Englewood station, on the curve where the New York Central, coming from La Salle Street Station, turned southeast to parallel the Pennsylvania Railroad into Indiana — a spot familiar to me from visits there with my father in post-World War II days. Judging from the angle of the shadows the time is about 4:00 p.m., the time of the departure of the Twentieth Century Limited from Chicago after the introduction of the J-3s shortened the schedule between Chicago and New York to 16 hours. After a run of some 922 miles from Englewood to the steam terminal at Harmon, New York, the train would proceed under electric power into Grand Central Station, where its elite consist of passengers would receive the famous "red carpet treatment."

The J-3a class had dimensions differing slightly from those of the J-1s. The unstreamlined members of the class weighed less, at 360,000 pounds, since the shrouding of the streamlined members raised the weight to 365,500 pounds. They had 22½x29-inch cylinders, and the boiler pressure was raised to 275 pounds (soon lowered to 265 when it was found that the extra "punch" actually bent the locomotives' rods). Although their tractive effort without booster was somewhat lower that that of the J-1s, with booster cut in it was slightly higher at 53,960 pounds. More importantly for the high-speed service for which these locomotives were designed, their steaming capacity rendered them capable of 4700 horsepower at 77 miles per hour, compared with 3900 horsepower at 66 miles per hour for the J-1 class. All the J-3s had roller bearings on all axles, but the last five, including No. 5450, had roller bearings on their connecting and coupling rods as well. In 1939 artist Charles Sheeler created a painting entitled Rolling Power as part of a series of paintings published in Fortune magazine to celebrate American industry. The painting depicts the right trailing pilot truck wheel and first two drivers of No. 5450, with the cylinder and valve gear linkage. The oil-on-canvas painting is owned by the Smith College Museum of Art. |

|

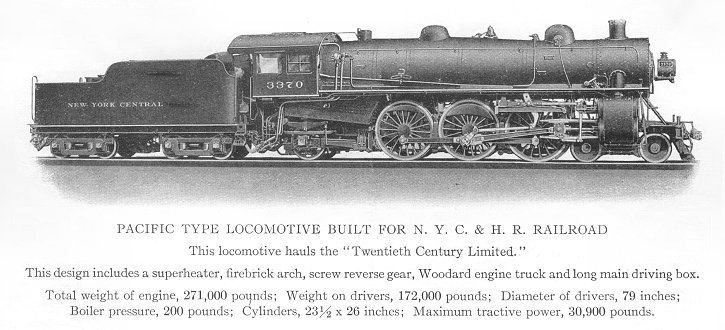

Before the advent of the famous Hudson type the premier trains of the New York Central's passenger fleet, including the Twentieth Century Limited, were hauled by Pacific or 4-6-2 type locomotives. The Central invested heavily in these engines, and in 1940 still rostered some 380 of them system-wide. Of this number, the most numerous were the 187 members of class K-3, which alone had 16 subclasses. This photo of Pacific No. 3328 (renumbered to 4728 in 1936) was taken in Butler, Indiana, in 1934. She was a member of class K-3n, erected by the American Locomotive Company's Brooks works in 1918. Engines of this class had 79-inch drivers, 200 pounds of boiler pressure, and cylinders measuring 23½x26 inches. They exerted a tractive force of 30,900 pounds to which a booster contributed another 9700 pounds. Butler, a small city in rural northeast Indiana, was not a stop for the Central's faster long-distance trains, so this photo shows No. 3328 (4728) heading a westbound local, the type of service to which the Pacifics were assigned after the Hudsons usurped their position on the premier "varnish." No. 4728 ras retired in 1950.

This photo came from my father's small collection, but whether he or another photographer took the picture is unknown. My mother's family was from Butler, but until my father met my mother a year later he would have had no occasion to visit the town for family reasons. It is possible that Dad and a friend drove through Butler on U.S. Highway 6 while returning east from their visit to the Century of Progress Exposition, and he might have snapped the picture then.

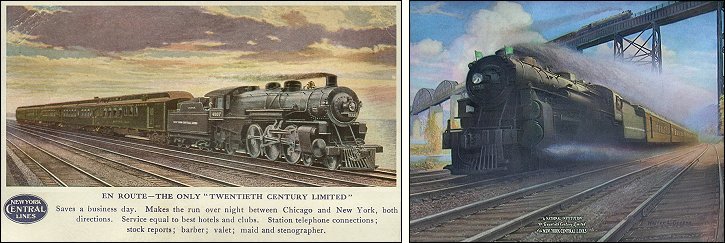

The NYC's premier Twentieth Century Limited service offered telephone connections at stations, barber, maid, stenographer, and — in thoughtful accomodation to the train's regular clientele — stock reports. The famous train was often featured in company publicity. The post card at left, mailed in October 1911, shows the Century speeding along the NYC's four-track main line with a K-3 Pacific in the lead (numbered 4807 in the painting). At right is a scene from the New York Central's 1926 calendar, by artist Walter L. Greene, showing K-3n Pacific No. 3292 (later 4692) racing south along the Hudson River under the recently constructed Castleton Cutoff bridge with the first section of the Century (the green flags indicate a following section). The artist depicted a four-track main line, but this section never had more than two tracks. The Greene print is shown here courtesy of Paul, Jr. and Jan Ubermuth of Connecticut.

The vast majority of New York Central's locomotives were built by the American Locomotive Company, which in 1913 published a catalog of examples of the Pacific type locomotives it was promoting. The above halftone from a 1913 bulletin of the American Locomotive Company shows No. 3370, a member of one of the earlier K-3 subclasses erected from 1911-1913 for NYC predecessor New York Central & Hudson River Railroad. As is evident from the photo of No. 3328 (4728) above, the original trailing truck for the K-3s was later replaced by a one-piece Delta casting and the early electric headlight was upgraded. |

|

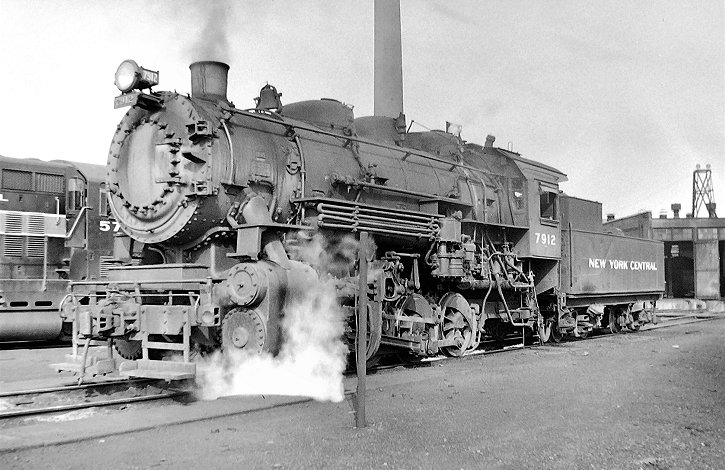

The New York Central System's fleet of class H (2-8-2 type) locomotives was built in the 1910s and 1920s for main line freight service, but most were soon supplanted in that role by the Mohawks (4-8-2 type) and, on the Boston & Albany, the Berkshires (2-8-4 type). Nevertheless they soldiered on into the beginnings of the diesel era in local freight, branch line or yard transfer service. Indeed, a class H-7 2-8-2 was the last steam locomotive to be operated by the New York Central. My first cab ride, at the age of eight or nine, was in class H-10b locomotive No. 2345 at Jackson, Michigan, through the courtesy of an engineer my father had befriended.

Our visit to NYC's Detroit engine terminal in March, 1954, yielded this shot of No. 1306. She was a member of class H-5j, a 1913 product of the American Locomotive Company, formerly Boston & Albany No. 1202 and renumbered in 1951 into the slot formerly occupied by H-5n No. 1306 which was scrapped in 1949. These engines rolled on the 63-inch drivers that were standard for New York Central's 2-8-2s. The H-5j class had 25x32-inch cylinders and 180 pounds of boiler pressure, and weighed 283,500 pounds. The NYC preferred the Baker valve gear on its newer locomotives, and retrofitted some of its older power (the earlier J-1 Hudsons) with that type of valve motion. In this photo No. 1306's Walschaerts valve gear, in reverse position, is clearly displayed. While no photo of this engine in its former B&A identity as No. 1202 has come to light, you can view an image of sister 1209 by noted rail photographer H. W. Pontin in our New York Central Collection if you click here. |

|

0-8-0 No. 7538 was a member of class U-2g, erected by Lima Locomotive Works in 1918 (note the diamond-shaped builder's plate). This group had 58-inch drivers and sustained 185 pounds of boiler pressure. They had 23½x30-inch cylinders and weighed 218,000 pounds, and exerted a tractive force of 44,920 pounds. For some reason I have no record of when and where I photographed No. 7538, but I believe it was in Lansing, Michigan in August 1953. It appears that this engine and its companion were out of service at this time, stored outside the roundhouse.

Our March, 1954 visit to the Detroit engine terminal found several tracks lined with "dead" steam engines awaiting their final trip to the scrap yards. Among them was 0-8-0 switcher No. 7718. Normally, locomotives destined for scrapping had their valve gear disconnected from the eccentric crank, allowing them to be towed with less cylinder resistance. No. 7718, however, was still intact. She belonged to class U-3c, delivered in 1922 by American Locomotive Company and Lima Locomotive Works. The U-3 class, numbering some 417 locomotives systemwide, all had 52-inch drivers and 25x28-inch cylinders. No. 7718's group had a boiler pressure of 175 pounds per square inch and a locomotive weight of 219,500 pounds, and produced 50,060 pounds of tractive effort.

|

The proper term is "pilot," but the fixture on the front end of a steam locomotive was often called the "cowcatcher," a throwback to the early days of railroading. The flared and spoked device, originally much larger, was supposed to sweep obstacles, especially stray livestock, from the tracks or at least cushion the rest of the locomotive from impact. Most of the NYC's L-2s, being used in freight service, had footboards on the pilot, useful to trainmen in switching maneuvers, but No. 2967 displays the familiar "cowcatcher" pilot. Some members of the L-2c and L-2d class had these pilots, especially on the former Michigan Central. Although usually this type of pilot was fabricated from boiler tubing or other extruded material, it could be a steel casting as on newer NYC locomotives. However, on its older power the New York Central used wooden pilots, painted black. In the late 1940s my father took me to visit the New York Central's shop complex in Jackson, Michigan. Outside one of the shop buildings we were surprised to see new, unpainted wooden cowcatchers destined for mounting on locomotives undergoing repairs.

The proper term is "pilot," but the fixture on the front end of a steam locomotive was often called the "cowcatcher," a throwback to the early days of railroading. The flared and spoked device, originally much larger, was supposed to sweep obstacles, especially stray livestock, from the tracks or at least cushion the rest of the locomotive from impact. Most of the NYC's L-2s, being used in freight service, had footboards on the pilot, useful to trainmen in switching maneuvers, but No. 2967 displays the familiar "cowcatcher" pilot. Some members of the L-2c and L-2d class had these pilots, especially on the former Michigan Central. Although usually this type of pilot was fabricated from boiler tubing or other extruded material, it could be a steel casting as on newer NYC locomotives. However, on its older power the New York Central used wooden pilots, painted black. In the late 1940s my father took me to visit the New York Central's shop complex in Jackson, Michigan. Outside one of the shop buildings we were surprised to see new, unpainted wooden cowcatchers destined for mounting on locomotives undergoing repairs.

The textbook goes on to describe in detail the operation of locomotive stokers and water systems, techniques for firing different kinds of coal, how to control the fire and the use of the grates, the ash pan flusher and coal pusher, how to control sludge and foam in the water supply, reading the pyrometer (temperature gauge for superheated steam), how to avoid plugging of the smokebox netting, and smoke and draft control.

The textbook goes on to describe in detail the operation of locomotive stokers and water systems, techniques for firing different kinds of coal, how to control the fire and the use of the grates, the ash pan flusher and coal pusher, how to control sludge and foam in the water supply, reading the pyrometer (temperature gauge for superheated steam), how to avoid plugging of the smokebox netting, and smoke and draft control.

I have a photo of another streamlined Hudson taken the same day and location, so whether this locomotive is heading the on-schedule Century, a section of it, or possibly another train is impossible to determine. A vignette of No. 5450 at this same location appears in the Herron video The Glory Machines 3, and she is also shown in the now hard-to-find Chicory Productions The Century of the New York Central, Part I. According to information from George Elwood's

I have a photo of another streamlined Hudson taken the same day and location, so whether this locomotive is heading the on-schedule Century, a section of it, or possibly another train is impossible to determine. A vignette of No. 5450 at this same location appears in the Herron video The Glory Machines 3, and she is also shown in the now hard-to-find Chicory Productions The Century of the New York Central, Part I. According to information from George Elwood's  The lowly switch engine lacked the glamour attached to heavy main-line freight locomotives or high-speed passenger power. Nevertheless, if these workhorses had not performed their mundane assignments in yards, terminals and industrial trackage, the larger road engines would have had nothing to haul. The New York Central had hundreds of

The lowly switch engine lacked the glamour attached to heavy main-line freight locomotives or high-speed passenger power. Nevertheless, if these workhorses had not performed their mundane assignments in yards, terminals and industrial trackage, the larger road engines would have had nothing to haul. The New York Central had hundreds of  At Kankakee, Illinois, in the summer of 1955,

At Kankakee, Illinois, in the summer of 1955,