E-Mail Us:

railarchive@mail.com

Text and photo images

©2013 Richard Leonard.

Although my primary rail attraction has always been the steam locomotive, by the mid-1950s this species had become so scarce that I was usually reduced to photographing diesels and other items of interest on or along the right-of-way. In the process I somehow managed to collect a few items that turn out to be of antiquarian value six decades later. I can't expect you to enjoy them as much as my steam collection, but here they are.

Bloomington, Illinois, in the mid-fifties was still an important terminal for the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad, the midpoint on its former Alton Route main line between Chicago and St. Louis. The "twin cities" of Bloomington and Normal are home to two universities, and Bloomington was a principal stop for the GM&O's famous Ann Rutledge, Abraham Lincoln, Alton Limited and other passenger trains which at that time blazed across the prairie at 90 miles per hour on well-maintained double track.

From Bloomington another line branched off to the southwest through rural terrain on its way to Jacksonville and a connection with the line to Kansas City. The flat-switched freight yard with its control tower was always busy collecting and sorting cars, and the crash of couplers could be heard from blocks away through the open windows of a warm summer night. Also in Bloomington were the GM&O's shops, which still handled major repairs to both locomotives and rolling stock.  Having moved to Bloomington in 1954, I became a frequent visitor — via bicycle — to the Locust Street bridge overlooking the south end of the yard and the shop complex.

Having moved to Bloomington in 1954, I became a frequent visitor — via bicycle — to the Locust Street bridge overlooking the south end of the yard and the shop complex.

From that vantagepoint I spotted a rare find, the original high-speed passenger diesel locomotive that was not part of an articulated train set. Built by Electro-Motive in 1935 as Baltimore & Ohio No. 50, this 1800-horsepower twin-engine locomotive was first placed in service between New York and Washington hauling the Royal Blue. During that time the B&O controlled the Alton Railroad, and in 1937 the locomotive and its train were sent to Illinois where they became the Alton's Anne Rutledge. The Alton redesigned the front of No. 50 in the "shovel nose" style of some early diesel streamlining (shown at right), and in that guise it graced the front cover of Alton Route timetables and was assigned to the Abraham Lincoln. Reportedly the unit was renumbered to No. 100 and, in 1946, to No. 1200, the number it retained after the Alton was absorbed by the GM&O in 1947. Subsequently the locomotive was restored to its original B&O configuration, though decked in the GM&O's red and maroon livery. It was in that final operating stage that I photographed it in May, 1955. Withdrawn from service a few years later, it is now displayed at the National Museum of Transportation in St. Louis, repainted to its B&O blue and bearing its original number.

For more photos of the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio in central Illinois in the 1950s, visit Richard Leonard's GM&O Gallery.

|

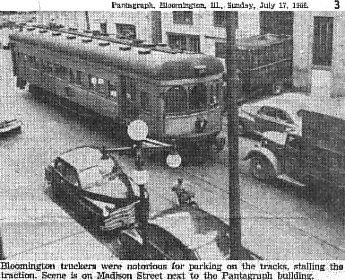

Known as "the Traction" from its former name, the Illinois Traction System, the Illinois Terminal remained alive in the memory of Bloomington citizenry. In 1966, the Bloomington Daily Pantagraph published a historical feature that included this photo illustrating the obstacles "the Traction" faced in threading its way through the city streets. Judging from the automobile styling, this picture was taken in the late 1940s. While it was not our privilege to see "the Traction" in operation, there was one two-block section of South Madison Street that remained under wire. Here the Illinois Power Company still used a small steeple-cab motor to switch coal hoppers from a siding on the New York Central's Peoria & Eastern branch to its city power plant adjacent to the tracks. I witnessed this operation several times and photographed Illinois Power Company No. 2 performing this duty in December 1954. |

Some years ago I chanced to meet the late Walter McClister, who retired in 1980 as foreman of the Illinois Terminal shops in Alton, Illinois. According to Mr. McClister, the Illinois Terminal sold this locomotive to the power company in the late 1930s but continued to maintain it. It was known as "the goat" and had an air compressor in one end, which would have been used to supply the brake lines. (Mr. McClister passed away in January 2010.)

The Baldwin Locomotive Works, a leader in the production of steam locomotives, entered the diesel market too late to survive long in an industry dominated by General Motors' Electro-Motive Division and, to a lesser extent, the American Locomotive Company, and their Canadian affiliates. With some exceptions usually due to wartime restrictions, steam locomotives were custom-built for each railroad, and in the early to mid twentieth century each major line's motive power fleet had its characteristic "look." By contrast, the successful diesel builders marketed the same line of models to the entire railroad industry, resulting in cookie-cutter locomotive fleets distinguished only by their paint jobs. Baldwin, however, carried the "tailor made" philosophy into its earlier diesel production, a strategic error that resulted in the creation of some distinctive designs that were sold only to a handful of railroads. One example was the famous "Shark Nose" style pioneered by the Pennsylvania Railroad — emulating its T-1 duplex drive steam engines — and another was the ponderous, multi-wheeled "Centipede."

A lesser-known Baldwin product was the "Baby Face" style, predecessor to the "Shark Nose," which existed in passenger and freight versions. The passenger version used on several railroads was the twin-engine, 2000-horsepower DR 6-4-2000. A unique double-cabbed, reversible version of the DR 6-4-2000 was used by the Central Railroad of New Jersey in commuter service, called the DRX 6-4-2000. Six of these units were built in 1946-48. The above photo of No. 2001 is a Jersey Central publicity photo the railroad's passenger department sent me when I wrote to them around 1952 asking for timetables for my collection. The freight model was sold in 1500-horsepower A (cab) and B (cabless) units, known as the DR 4-4-1500. The Jersey Central operated fifteen of these (ten A and five B units), and the Pennsylvania and the Missouri Pacific also used them. The New York Central had four A and two B units, and I happened to photograph A units Nos. 3800-3801 during a family visit to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in August 1955. None of these "Baby Face" units survive. To view some of the Baldwin units in the DR series, visit North East Rails' Baldwin Cab Diesel Railroad Locomotives page.

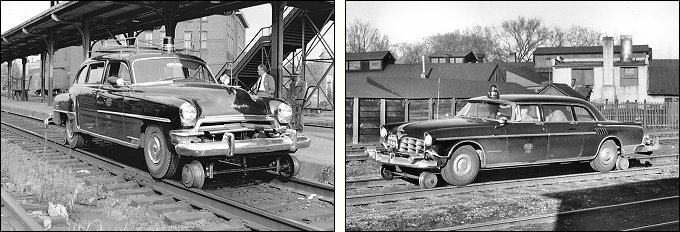

From time to time railroad officials need to inspect the right-of-way and facilities in order to monitor conditions on the lines they manage. Over the decades they have used a variety of means of transport in performing this duty. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, a small steam locomotive was sometimes surrounded with a coach body to serve as an inspection engine. I can remember my father relating that he rode in one of these as a boy with my grandfather, then an official of the Boston & Albany.

By the time I was archiving assorted railroad operations in the 1950s, the mode of transportation for this purpose had shifted to internal combustion. The New York Central System seems to have favored the Chrysler Imperial, fitted with flanged guide wheels, as the vehicle for its inspecting officials. On two separate occasions I photographed these specially equipped cars. At left, car M-100, a 1954 Imperial, is shown at the depot in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in August 1955. An article in the June 1957 issue of Trains shows this car, or a slightly later model, in use as an inspection car by the New York Central's president, the legendary Alfred E. Perlman. Whether he was present when I took this photo is uncertain; the gentleman standing behind the car does not appear to be Mr. Perlman, but he might be the man whose arm appears in the window on the passenger side. Inspection car X-104, shown at right in Bloomington, Illinois, was a 1956 Imperial heading for Peoria on the New York Central's former Peoria & Eastern branch in April 1958. Seated within are several officials wearing suits and hats.

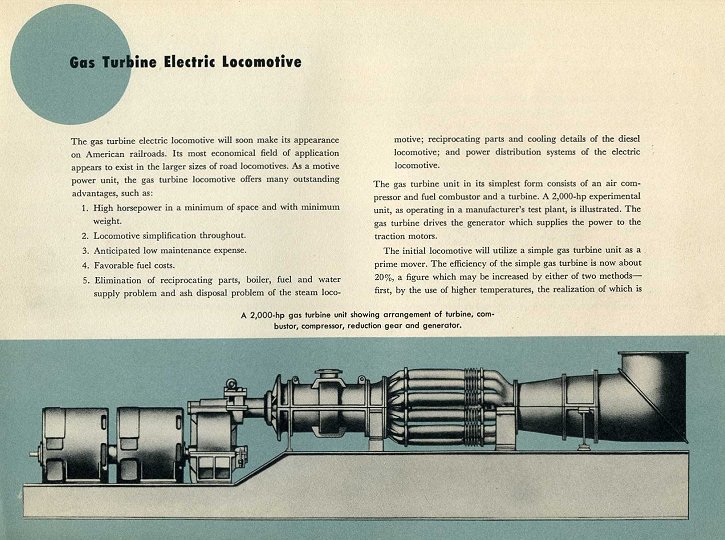

Steam, diesel and electric propulsion were not the only railroad motive power options in the 1950s. In a booklet published by Westinghouse Electric Corporation in 1948, Modern Developments in Railroad Motive Power, the company asserted that "the gas turbine electric locomotive will soon make its appearance on American railroads." The Westinghouse drawing depicts a projected 2,000-horsepower turbine driving generators at the left.

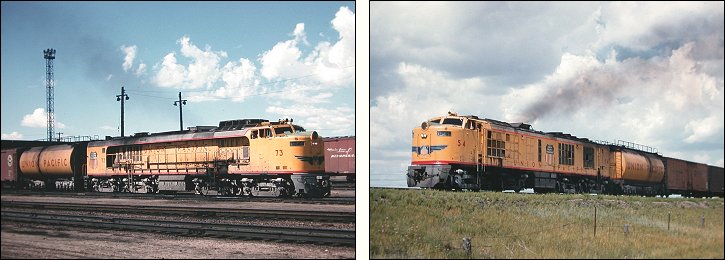

A Westinghouse demonstrator was finally completed in 1950, with two 2000-horsepower turbines. It was tested on several railroads in both passenger and freight service, but due to high operating costs it was scrapped in 1952. More successful, however, was the 4500-horsepower gas turbine demonstrator built by General Electric in cooperation with the American Locomotive Company. After tryouts on a number of railroads it was placed in service on the Union Pacific in 1949. Subsequently the UP operated 56 gas turbines of three types. I captured No. 73, of the second group, on Kodachrome transparency in August 1957 at Laramie, Wyoming. This group was distinguished by its covered walkway, and is therefore sometimes known as the "veranda" type. Following No. 54, of the earlier group, out of the yard with its train we photographed it on the hill east of Laramie.

In these locomotives the turbines drove generators that supplied power for the traction motors in four trucks, or sets of wheels and axles. In the earlier groups all four trucks were under the same car body, as with No. 75; in the last group, the locomotive was in two units each having two trucks. The turbine locomotives burned a low-cost fuel, but required so much of it that they were equipped with tenders like a steam locomotive and, indeed, the Union Pacific re-used tenders from scrapped steam engines on some of the gas turbines. They were heavy haulers and the final class achieved 8500 horsepower. However, because of the high-pitched whine of the turbines they were considered too noisy for use in heavily populated areas (I was told they were banned from Denver) and could only run on the open Western plains. As locomotives the gas turbine electrics were successful, but by 1970 the last group had been retired in favor of diesel power. (To view more photos of the UP's different turbine classes, visit our Union Pacific Gas Turbines page; North East Rails' Turbine Railroad Locomotives page, and Don Ross's Union Pacific Turbines page.)

|

As replacements for the gas turbines that were being phased out the Union Pacific acquired a penchant for ordering some rare diesels. One such model was the General Electric U50. These locomotives were essentially two GE U25 locomotives in one unit. They had two 2500-horsepower diesel engines and generators, each of which powered two trucks at one end of the locomotive. The running gear was reused from turbines that had been scrapped. The B-B+B-B arrangement made for a total unit horsepower of 5000.

The 23 engines of Union Pacific's U50 series were delivered by General Electric in three groups beginning in 1963. I took this transparency of No. 45, last of the second group delivered in 1964, somewhere in northeastern Kansas in the early 1970s not long before most of these units were withdrawn from service. All were retired by 1977. |

|

By the 1920s North American railroads were beginning to feel the pinch of the private automobile, which began to draw passengers away from trains especially for local or short-distance travel. One response was to reduce the railroad's costs by transitioning from locomotive-hauled trains with standard equipment to the new self-propelled railcars being developed by General Electric, the Electro-Motive Company and other builders. These vehicles, popularly known as "doodlebugs," were operated by both Class 1 and short line railroads and were especially popular on lightly traveled lines in the West and Midwest. Most of these self-propelled trains were powered by gasoline or distillate engines generating power for electrical transmissions. By 1927 more than 200 had been placed in service. Later models were diesel-powered, and some had direct mechanical transmissions. In level territory the self-propelled car could haul one or two trailing coaches. During the mid-twentieth century, heavy regulation by the Interstate Commerce Commission often made it a difficult and time-consuming process to discontinue unprofitable passenger service, and the "doodlebug" helped the railroads to reduce their losses.

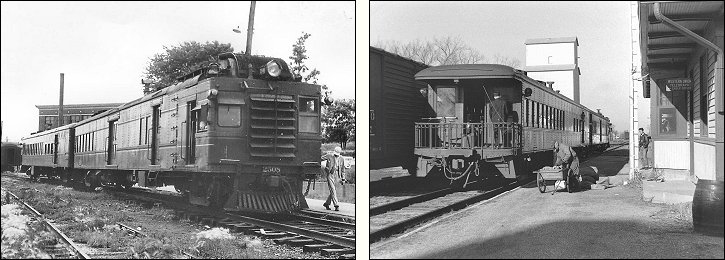

Until 1960 the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio was still operating passenger service between Bloomington and Kansas City via Jacksonville, Illinois, using Electro-Motive diesel-electric cars with trailers. On a June day in 1959, my brother and I had a chance to ride the "doodlebug" from Bloomington down to Jacksonville, where our father had driven to attend the Methodist annual conference session. The photograph at left shows unit No. 2508 at the depot in Bloomington, ready to depart with us on its bucolic journey. It was good that we took advantage of this opportunity, for within a year the service would be discontinued. In the photo at right, taken some time before our trip, the train pulls away after stopping at Stanford, first regular stop west of Bloomington. For more photos of the GM&O's Jacksonville line in the 1950s, visit Richard Leonard's GM&O Gallery. |

The FA freight unit was the American Locomotive Company's best-selling entry into the first-generation diesel market. Although ALCo's offering could not compete in numbers with Electro-Motive's popular F unit, 864 A units were sold along with 490 B units. The successive models of the FA ranged from 1500 to 1800 horsepower. Enthusiasts have called it "one of the most handsome diesel locomotives ever built." (For more information on the FAs and other diesel cab units, go to Brent Holt's Exotic Diesel Locomotives site.)

The New York Central, a staunch American Locomotive customer in steam days, was one of the heavier users of the FA unit. Although the FA was not exactly a rarity, I couldn't resist including this photo of a four-unit ALCo lashup in the yard at Pittsfield, Massachusetts in August 1955. No. 1018 is trailed by B units 3333 and 3334 and A unit 1036. This eastbound freight is about to remount its attack on the Berkshires. The dominating semaphore tower, the moving freight in the background, and the trainmen conferring at the head of their ready-to-roll steed combine to render this — in my judgment — one of my best railroad compositions.

The Illinois Terminal Railroad was one of the last of the Midwestern electric interurbans, surviving into the 1960s after conversion to diesel power and continuing to operate until absorption by the Norfolk & Western in 1982. Connecting the major cities of central Illinois including Peoria, Decatur, Springfield and East St. Louis, its trackage — like that of most interurban railways — usually paralleled that of the "steam railroads" in rural areas but borrowed local street car tracks through cities. The Illinois Terminal had a line from Decatur through Bloomington to Peoria, but when my family moved to Bloomington in 1954 we found that service had been discontinued the year before. Several streets with tracks in them were almost the only vestige of what had once been a popular local mode of transportation.

The Illinois Terminal Railroad was one of the last of the Midwestern electric interurbans, surviving into the 1960s after conversion to diesel power and continuing to operate until absorption by the Norfolk & Western in 1982. Connecting the major cities of central Illinois including Peoria, Decatur, Springfield and East St. Louis, its trackage — like that of most interurban railways — usually paralleled that of the "steam railroads" in rural areas but borrowed local street car tracks through cities. The Illinois Terminal had a line from Decatur through Bloomington to Peoria, but when my family moved to Bloomington in 1954 we found that service had been discontinued the year before. Several streets with tracks in them were almost the only vestige of what had once been a popular local mode of transportation.