Smoky locomotives could be a vexation to travelers riding in their finest clothing, and also to housewives who had to hang out their white sheets to dry near a railroad track. Some eastern railroads burned anthracite, which was more environmentally friendly because it produced less smoke than bituminous coal. But because anthracite burned cooler than coal, locomotives that used it had to have wider fireboxes to generate the same amount of steam. In many cases the width of the firebox left no room to mount the engineman's cab over it. The solution was to move the cab forward to the middle of the boiler, leaving the unhappy fireman to stoke the fire from his small open-air enclosure at the rear of the locomotive. For that matter the engineer, riding above the driving wheels, might be nervous about a rod coming loose and penetrating the floor of his cab. This type of engine was known as the "Camelback." A major user was the Central Railroad of New Jersey; as late as 1950 around half its steam locomotives were Camelbacks.

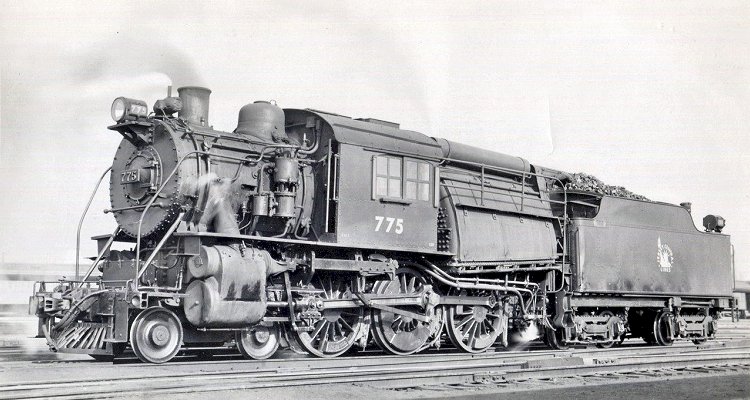

Jersey Central Ten-wheeler No. 775, of the T-38 class (originally L7as), illustrates the Camelback design in this image from Frank Fabian, via Wayne Koch. Built by Baldwin in 1913, she had 69-inch drivers, 23x28-inch cylinders, and 210 p.s.i. of boiler pressure. The 91.4-square-foot grate area of her firebox was considerably larger than that of most 4-6-0s, and she weighed 225,600 pounds without tender. The T-38 class had 2306 square feet of evaporative heating surface plus 477 square feet of superheater surface, and exerted 36,493 pounds of tractive force. Despite these modest dimensions, Camelbacks like No. 775 persisted in commuter service out of the Jersey City terminal until the end of steam on the Central Railroad of New Jersey.